Shi Xinchuan, the owner of a hardware store in northern Vietnam, spends a lot of time these days sitting alone in his empty shop, while his mind fills with anxious theories about who will get hurt – and how badly – by US tariffs.

Since he moved from his native China, the 24-year-old has made a living by supplying companies in the city of Bac Ninh with adhesives, electronic components and other goods.

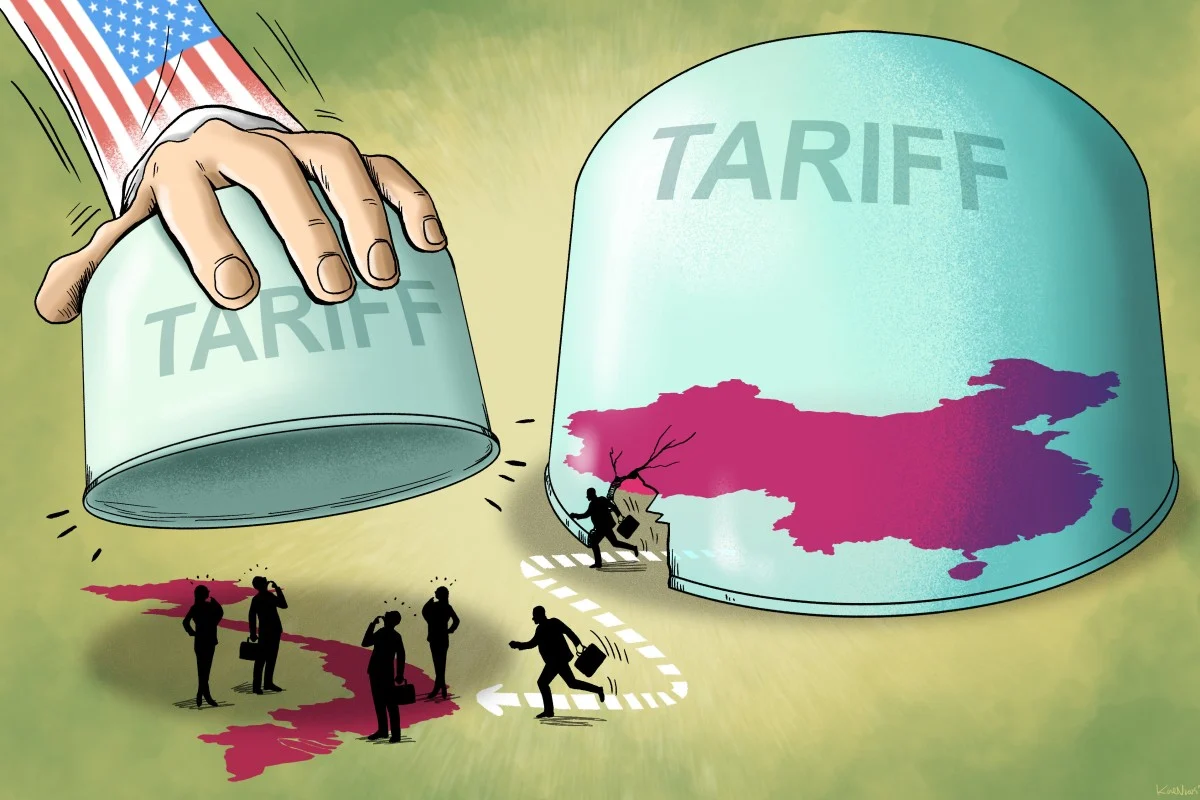

But many of his localised Chinese clients are now facing a crisis as US President Donald Trump’s aggressive trade policies threaten to upend Vietnam’s vast export sector.

“Chinese companies here are waiting, observing for the next two months,” Shi said as he made a pot of tea. “They’re afraid, yes they’re afraid.”

These are tense, uncertain times for businesses in Bac Ninh. The city of nearly 250,000 people has emerged as a thriving factory hub over the past few years, as Chinese manufacturers moved into the area in search of a tariff-free route to the US market.

Now, that path risks being closed off. In early April, Trump announced plans to slap a 46 per cent levy on imports from Vietnam – one of the highest rates imposed in his so-called “reciprocal” tariff plan.

Though Washington has since paused the reciprocal duties for 90 days, they have not been cancelled and continue to hang over the heads of exporters in Vietnam. Unless Hanoi can strike a deal with Washington, the tariffs will come into force in July.

Local businesses are already feeling the effects. Though some factories have seen a short-term spike in orders during the 90-day grace period, other Chinese companies have frozen their expansion plans or withdrawn from Vietnam entirely, analysts and businesspeople on the ground said.

Shi, whose family also runs a separate business holding events for Chinese investors looking to set up operations in Bac Ninh, said some of those clients were likely to fold if the US tariffs return in the summer.

“If the tariffs hold at 46 per cent, it’s definitely going to be tough for smaller low-margin sellers like textile makers,” said Dan Martin, a Hanoi-based international business adviser with Dezan Shira & Associates. “You could see it being a major issue.”

Everyone is talking about tariffs in Bac Ninh these days, said Xiao Hao, a barber who moved to the city from central China’s Hunan province in April. “What Trump is doing, of course it impacts all of us,” he sighed.

Chinese exporters in Vietnam have no easy options. Many of them have invested heavily to set up facilities in the Southeast Asian nation since 2018, when Trump launched a trade war against China during his first term in office.

And returning to China will not help most firms, as Washington has hit Chinese goods with even steeper tariff hikes that have brought the total effective rate to as high as 156 per cent in many industries, though some goods have been exempted.

For now, most businesses in Bac Ninh are sitting tight and anxiously waiting to see if Hanoi can convince Washington to scrap – or at least lower – the reciprocal tariffs targeting Vietnam.

The Vietnamese government moved swiftly to lobby the US for a deal, with Deputy Prime Minister Ho Duc Phoc meeting with US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent as early as April 10 as both sides agreed to begin formal discussions.

Hanoi has reportedly offered Washington a string of concessions to secure tariff relief, including cutting its duties on US products such as cars and liquefied natural gas and granting approvals to Elon Musk’s Starlink satellite internet service.

Though the two governments have yet to confirm an agreement, some Chinese investors in Bac Ninh expect the 46 per cent tariff will be cut by half or more.

But Vietnam’s close relationship with China could be a complication. When President Xi Jinping met with leaders in Hanoi last month, Trump suspected the two sides were discussing how to take advantage of the US.

Beijing, for its part, has urged its trade partners not to sign deals with the US “at the expense of China’s interests”.

Ultimately, US tariffs on Vietnam “are going to come down, but I’ve heard no magic figure”, said Carl Thayer, an emeritus professor of politics at the University of New South Wales in Australia, whose research focuses on Southeast Asia.

The final number will be crucial. A 46 per cent tariff would wipe out the profits of many Chinese companies in Vietnam, experts said. A lower tariff “is still painful for a lot of firms, but for larger ones it’s not a deal-breaker”, Martin said.

Other details of a potential deal could also have far-reaching implications for exporters in Bac Ninh, such as US regulations regarding what constitutes a made-in-Vietnam product.

Washington has expressed concerns at points about Chinese companies using Vietnam to transship made-in-China goods to the US, allowing them to evade American tariffs targeting China.

But it is more common for factories in Vietnam to add value to unfinished Chinese goods, so they officially count as made-in-Vietnam products, analysts said.

Currently, products must be at least 30 per cent locally made to be classified as Vietnamese goods by US customs. There is talk of Washington raising that threshold, although it is unclear to what extent US officials care about this practice, according to Martin.

If the local content rules are tightened, it could cause another wave of upheaval in global supply chains, given the sheer number of Chinese exporters operating factories overseas.

In April, Goldman Sachs estimated that 20 per cent of the Chinese producers they were tracking were using offshore facilities – especially in Southeast Asia and Mexico – to reduce their tariff burdens.

For now, most Chinese-invested companies in Vietnam plan to continue operating as usual, but hold back on any new investment plans until the tariff negotiations end, analysts said.

“It’s not that easy to change your orders,” said Adam McCarty, chief economist with Mekong Economics in Hanoi.

In Bac Ninh’s city centre, Chinese business travellers can still be seen buzzing in and out of local hotels and holding meetings at the city’s scores of outdoor cafes.

Staff working for Goertek, a Chinese maker of electronic parts that operates a sprawling green-and-white factory compound in the suburbs, said business was humming along normally.

Liu Wenping, business director of a local metals trading firm, said that his company was doing fine but that some clients were struggling. “The impact is pretty big, and some people have taken off,” he said.

Ming Ying, who works for a Vietnamese consultancy that helps Chinese newcomers to set up a local business, said that the company was receiving fewer inquiries compared with early 2024, as investors were worried about the tariffs.

Some Chinese companies have already priced in a tariff of 20 to 30 per cent, as they believe they can absorb the cost, said Liu Jie, who runs an offshore brand marketing company with offices in Hanoi.

But Liu added that he also knew of a 1,000-person delegation from China that cancelled a fact-finding mission to Vietnam, as they no longer intended to set up a factory in the country.

Producers in Bac Ninh have reacted differently to recent events, according to Liu. Some have accelerated their US orders to take advantage of the 90-day tariff freeze, while others have cancelled orders.

Chinese customs data show large jumps in shipments to Vietnam ahead of the tariffs coming into force, as producers rush to front-load orders. Exports of computer parts were up 125 per cent year on year in March.

If the US does go ahead with tariffs on Vietnam, Chinese companies in the country may survive by rebuilding their supply networks to cut out America, Martin said. They might also pivot to selling to Asia or Europe rather than the US.

But Wu Lingyun, Shi’s uncle and general manager of the family events business, said that “the US is still the major market” for firms in Bac Ninh.

“Why do Chinese companies come to Vietnam?” he said. “It’s for that, like Apple, Microsoft and Tesla. The profits are a bit higher.”